So… we closed our doors rather unexpectedly a few months back for an extended summer vacation, something we then decided that we love and will likely make a regular occurrence of in the future (though much, MUCH shorter), because let’s face it, summertime should be about family, sunshine, adventures, and reading good books, rather than sitting in a gloomy subterranean room writing about them. That said, the leaves are turning and now we’re back, and we have some very exciting things planned for the next nine and a half months before we once again vanish into the internet ether.

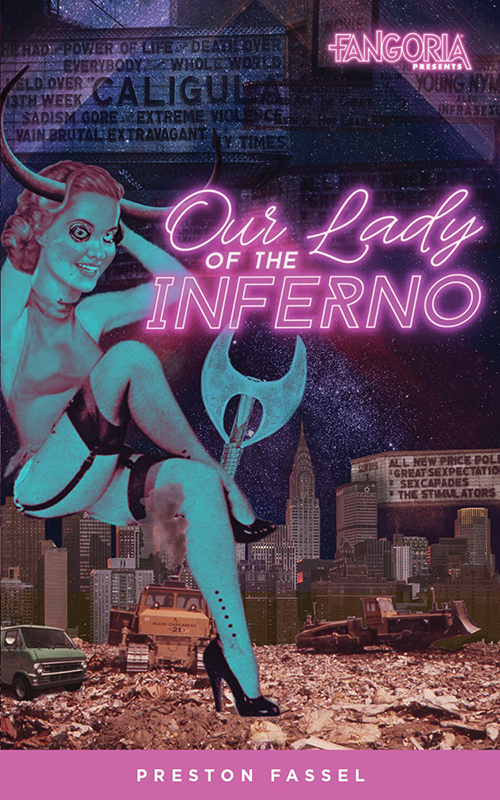

But first we must celebrate the book birthday of Preston Fassel’s Our Lady of the Inferno, which now amazingly has two different book birthdays as this latest release from Fangoria marks the second time the novel has been reissued. If you like gritty period pieces featuring tough-as-nails women, you need to take a stroll down to New York’s 42 St. with Fassel’s Inferno. To celebrate the novel’s big day, here’s a Q&A I conducted with the author on the eve of the book’s second release. (Note: Small portions of this interview ran in the Library of the Damned column in Rue Morgue #182).

What attracted you to write a period piece set on New York’s 42nd St. in 1983?

What attracted you to write a period piece set on New York’s 42nd St. in 1983?

I’ve been interested in the history of 42nd Street, and the grindhouse/vice culture in particular, ever since I read Bill Landis and Michelle Clifford’s Sleazoid Express in high school. I’ve always been interested in subcultures, and the idea that there was this whole sort of kingdom of the damned that existed in New York and was partially built around low-rent horror movies and pulp filmmaking was absolutely astounding to me. Throughout college, I had short stories published in my campus’ literary magazine about people working in a movie theatre on 42nd Street in 1977, and tried to turn them into a novel, with no success. I worked on the book from 2007 to 2012 and by the time I gave up I had 250,000 words, twenty main characters, and no plot. A lot of it, though, prepared me for writing Our Lady; I don’t think I could’ve written it if I hadn’t have had that failure.

That it’s set in 1983 is a happy accident. When I began writing the book, I hadn’t intended to ever specify exactly what year it was taking place. It was just going to be “the 80s.” I grew up on all manner of ’80s movies, horror and otherwise, and for someone who had a not-so-great childhood, those movies specifically and the pop culture of the decade in general were this escape for me. I wanted to pay homage to that. There was a point in the story where I needed Ginny to cite a female role model and the first person to come to mind, since she’s a science lover, was Sally Ride. I went to double check and make sure that Ride’s space flight was in fact in the ’80s, and realized she’d gone up the same year that Flashdance came out. I had, at a certain point in the writing process, conceptualized the story as “Flashdance meets Silence of the Lambs,” and always intended to put a Flashdance nod in there, so it seemed appropriate I just set it in 1983 against the backdrop of all these historical events.

How much research did the book require, given its focus on prostitution and seedier sides of NYC life?

Technically speaking, something to the tune of like six years worth of research went into the book, because the entire time that I was writing that theatre story, I was doing research on 42nd Street in the 1970s and ’80s. In addition to Sleazoid Express, I read Ghosts of 42nd Street by Anthony Bianco, period newspaper articles, watched old news footage, and found online communities dedicated to grindhouse movies and New York in the ’70s and ’80s. When I began writing Our Lady, the research only continued to fill out what I already knew about 42nd Street with what changes it underwent in the ’80s. Citydata.com, in particular, was very valuable, as I was able to ask people there about certain minute details that weren’t readily available in books or articles—like, for example, whether the Port Authority Bus Terminal sold coffee in 1983. I also made contact with a historian named Elizabeth McLeod, who gave me invaluable information as to how an old-school theatre would’ve looked and operated in the early ’80s. It was important for me that the book be as factually accurate as possible, and that any deviations from real life were intentional. I looked at calendars from 1983, figured out what days of the week each chapter would take place on, what phase of the moon it would’ve been, what constellations would’ve been visible from Staten Island, and looked at weather reports for those days (though I decided to have it rain at two points when, in fact, it was not raining those days). If you’re reading about a physical place in the book, and what it looks like, you’re essentially reading about a real place. The Staten Island Landfill is Fresh Kills Landfill, the Colossus Theater is based on the Roxxy grindhouse, and the Motel Misanthrope is a conglomeration of a couple of welfare hotels.

Why was it important to you to incorporate references to movies and comics, as well as classic mythology into your novel?

In a lot of ways, the grindhouse theatres were the lifeblood of 42nd Street. Prostitutes serviced clients there, drug dealers went there to peddle, junkies went there to buy and use, petty crooks would hide there from the cops. There were even those who, like Roger in the book, sort of lived in these places, buying a ticket for triple features and then spending their entire days there. So you had this subculture of vice that gravitated around the movies. It was their common frame of reference. Regardless of race, age, gender, or criminal status, you were watching these movies. It was the language of 42nd. To not have replicated that in the book would’ve been denying a huge part of what made the culture there so fascinating. Too, ’80s films are just a huge part of American culture. I made sure to mix grindhouse touchstones, like Hausu and Maniac, with the movies everyone would’ve been watching at the time, like Friday the 13th 3D, Flashdance, Return of the Jedi.

That you’re asking about the mythology aspect is funny because it’s what inspired the novel in the first place. I’ve always thought that a serial killer obsessed with The Minotaur would make an excellent horror villain. And then there was a Minotaur killer in Season 3 of Dexter who I thought was incredibly lame and underutilized, and then American Horror Story: Coven had its minotaur, which I also thought was handled poorly. I wanted there to be a story that fully exploited the horror potential of the Minotaur. So, I wrote it. In addition to the Greek mythology, I also worked in a lot of stuff about Catholicism in general and DANTE’S INFERNO specifically. It’s a very Catholic horror story, in the way that Flannery O’Connor’s stories were, just with more sex, violence, and cannibalism. My mother’s grandparents were Jewish converts to Catholicism and both religions and cultures have had a tremendous impact on my life in both positive and negative ways. Horror movies and books tend to look at the negative aspects of Catholicism, so I wanted to write a story that looked at the positive side.

The two central characters in Our Lady of the Inferno are women. As a man, what made you want to cast women as the protagonists to your story?

The two central characters in Our Lady of the Inferno are women. As a man, what made you want to cast women as the protagonists to your story?

As an adolescent I had a very complicated relationship with women. I always had a good relationship with my mother and several of my teachers, but then I also suffered various forms of abuse at the hands of many of my teachers, all of whom were women and all of whom seemed to be taking out their issues with adult men on pubescent boys. So by the time I was sixteen, seventeen, I had simultaneously very progressive views towards women and then also very unhealthy ones. I was on the road to being one of these MRA, Nice Guy assholes. Then when I got to college I met some very wonderful women who saw those negative attitudes in me but who also recognized that I wasn’t some lost cause and that it was coming from a place of deep woundedness. They helped me to come to terms with the abuse that had formed these views and to begin to heal in a number of ways. Consciousness raising, I guess you’d call it. That’s what led me to my interest in women in horror, which was sort of my beat at Rue Morgue for a while. I wanted to give back.

So flash forward to 2014 and I’m covering Texas Frightmare Weekend for Rue Morgue, and this recurring theme seemed to be developing that year about the lack of good roles for women in horror movies. I’d been thinking about my Minotaur serial killer story but was having trouble getting it off the ground. Then, when I was chatting with Jen and Sylvia Soska, I happened to mention that I’m Polish and Jen Soska told me that they’re Hungarian, and asked what my favorite Polish swear word is. She told me hers is “Kurva,” which means “whore.” A light bulb went off. My problem with the Minotaur story was I couldn’t figure out who my protagonist should be. But serial killers tend to prey on sex workers, and prostitution was a huge part of 42nd street life, and in horror stories sex workers tend to be treated as this afterthought—they’re the generic victims who’re killed so that the heroes can come in and save the day. These anonymous sacrifices. How powerful would that be to take a character who’d normally be faceless and give her full life? The seeds that would become Ginny Kurva were planted. And I began thinking about Night of the Comet, which is one of my all time favorite movies, and how fun and well-drawn the two female protagonists of that are. I decided I’d make my Minotaur killer story a story like that, with great, complex female characters. Then I decided to go a step further. I wanted it to be something unique. What if the killer were a woman, too, though? We all love our horror villains, but, where are the good female horror villains, who aren’t sidekicks or lackeys or just sexually obsessed weirdos in thrall to a more powerful male villain? If I was going to do something truly different, and really strike a blow for women in horror, then I needed to create a villainess, every bit as complex as the protagonist, just as powerful and evil as Patrick Bateman or Hannibal Lecter but acting completely of her own agency.

Are there certain inherent challenges to writing female characters as a man? If so, what are they and how do you as a writer overcome them?

There actually weren’t. I think the biggest impediment to men writing women is that men think there’s going to be an impediment. My wife are I were having a discussion once about whether the word “feminism” has become too politicized, and her response was, “Feminism, to me, is the belief that women are people.” And that’s really all that needs to go into writing a female character: you write her as a person. She may have faced different experiences and challenges because of her sex, but, that’s no different than writing about a guy who, say, has faced different experiences and challenges because he’s a war veteran, or because he came from a lower socio-economic status. You’ve just got to recognize those unique challenges—like how Ginny’s intelligence is constantly ignored in favor of her sex appeal, or how Nicolette has grown to view herself as literally monstrous because of body image issues. If you can write men who face unique challenges because of their background, you can write women. You just have to recognize that basic humanity.

Leave a Reply